A brief introduction to Rust

I heard of Rust back in 2015 at a meetup. I have since spent time with Rust on and off. In 2018, I had more time to explore Rust. Thinking of using blogging as a learning tool while going further down the rabbit hole of Rust, I setup this blog. In this post, I would like to briefly walk through some important features of the language.

A very brief history

Rust is a multi-paradigm system programming language focused on memory safety, speed and safe concurrency. Rust’s rich type system and ownership model grantees type and memory safety without garbage collector and runtime! According to the very first presentation deck on the language by the original designer, Rust is created out of frustration by lacking of memory safety and concurrency control in C++. Almost one decade after starting as a side project, Rust version 1.0 was released in 2015. As of writing this post, the stable version of Rust is 1.32. Starting off with C-like syntax and semantics borrowed from other good old languages, Rust evolves to, in my opinion, a type-safe, memory-safe system programming language with ML-family style syntax and Haskell style type system with zero-overhead.

Immutable by default

In Rust, variables are immutable by default. Once a value is bound to an identifier, the value associated with that identifier cannot be changed. Rust compiler will refuse to run the following program giving error message “error[E0384]: cannot assign twice to immutable variable x”.

fn main() {

let x: i32 = 7;

x = 10; // error here

}

If you want to make your variables mutable, you need to explicitly declare them with mut keyword.

fn main() {

let mut x: i32 = 7;

dbg!(x); // `dbg!` is a macro to inspect a value or an expression for quick and dirty debugging.

x = 10;

dbg!(x);

}

🦀 Output:

[src/main.rs:3] x = 7

[src/main.rs:5] x = 10

Misusing mutability can introduce bugs which are hard to debug or fix. Rust suggests that you make variables mutable only necessary. It helps programmers to easily understand which parts of a program are moving and which parts are not. It can make Rust program easy to maintain and enhance. We can see a lot of needless mutable variables in programs written in a language where variables are mutable by default. Bug fixing and enhancing those programs unnecessarily require high cognitive load because we need to mentally keep track of all those incidental mutable variables. I find the reinforcement of immutability is one of the great features of Rust.

Data Types

Rust has data types and control flows we can find in most of the mainstream languages. It is notable that Rust doesn’t have class based user defined type.

Scalar Types

Rust has four scalar types:

- Boolean:

true, false - Integers( i for signed, u for unsigned) :

i8, i16, i32, i64, isize, u8, u16, u32, u64, usize(i32is default choice of Rust and perform faster than others)_ - Floating-point:

f32, f64 - Character: unicode scalar value like

‘a’,‘⌘’. Grapheme clusters, e.g.'é’, cannot be assigned to character type

A small but really handy one here is we can write numeric literal separated with underscore like 33_550_336. And numeric literals can be type annotated with type name suffix like 7i32 or 7_i32. Unsuffixed numeric literals will be basically associated with i32 for integers and f64 for floating point numbers if compiler is not able to infer the type.

fn main() {

let is_true = true;

let unity = 1; // unity is of i32 type.

let beta = 0.28016_94990; // beta is of f64 type.

let cmd_key = '⌘';

println!("is_true = {}, unity = {}, beta = {}, cmd_key = {}", is_true, unity, beta, cmd_key);

}

🦀 Output:

is_true = true, unity = 1, beta = 0.280169499, cmd_key = ⌘

Composite Types

Rust allows us to define types by grouping of same or different types. Rust has four built-in Composite types: tuple, array, struct and enum. Rust standard library includes lots of useful composite types too.

Tuple groups together unnamed but ordered values of same type or different types. Values of tuple can be retrieved through destructuring. In the following code snippet, a tuple golden_ratio is created and its values are destructured to symbol and value.

fn main(){

let golden_ratio = ("ϕ", 1.61803_39887);

println!("golden_ratio : {:?}", golden_ratio);

let (symbol, value) = golden_ratio;

println!("golden_ratio symbol : {}", symbol);

println!("golden_ratio value : {}", value);

}

🦀 Output:

golden_ratio : ("ϕ", 1.6180339887)

golden_ratio symbol : ϕ

golden_ratio value : 1.6180339887

Array is fixed-sized, zero-based sequence of elements which are all of the same type. Array size is part of the type and determined at compile time. Unlike C++ or C#, array in Rust is allocated on stack. If an array’s elements are accessed by indexing, Rust will check indices for out-of-bounds errors, and panic when the index is out of range. Array bound checking can be bypassed using get_unchecked method inside unsafe block if you want to remove the overhead. The following code snippet shows array declaration and mutation through indexing.

fn main(){

let even_under_ten : [i32; 4] = [2, 4, 6, 8];

/*

above line can be declared like `let even_under_ten = [2, 4, 6, 8];`

Rust compiler will deduces the type and size of the array

from right-hand side expression

*/

println!("even_under_ten = {:?}", even_under_ten);

// modify elements of a char array

let mut chars = ['a', 'b', 'c'];

println!("original: {:?}", chars);

chars[0] = 'x';

chars[1] = 'y';

chars[2] = 'z';

println!("modified: {:?}", chars);

// array of arrays

let matrix = [[1,2,4], [4,5,6]];

println!("matrix = {:?}", matrix);

println!("matrix first row = {:?}", matrix[0]);

println!("matrix second row = {:?}", matrix[1]);

}

🦀 Output:

even_under_ten = [2, 4, 6, 8]

original: ['a', 'b', 'c’]

modified: ['x', 'y', 'z’]

matrix = [[1, 2, 4], [4, 5, 6]]

matrix first row = [1, 2, 4]

matrix second row = [4, 5, 6]

Vector is array-like type but allocated in heap and growable in size. Vector is found at std::vec module in standard library.

fn main() {

let mut vec = Vec::new();

vec.push(1); // push method is used to add a single item

vec.extend(2..6); // extend method is used to add multiple items

println!("vec: {:?}", vec);

// using vec! macro

let nums = vec![1, 2, 3, 4, 5];

println!("num: {:?}", nums);

}

🦀 Output:

vec: [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

num: [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

Slice is a view of an array or a vector. Slice is written as [T]. Note that array is written [T; size] - e.g let array : [i32; 4] = [1, 2, 3, 4]. Being a view of an array or a vector, slice is not a type that can exist on its own. It has to live behind a pointer e.g &[T]. Slices are always passed by reference.

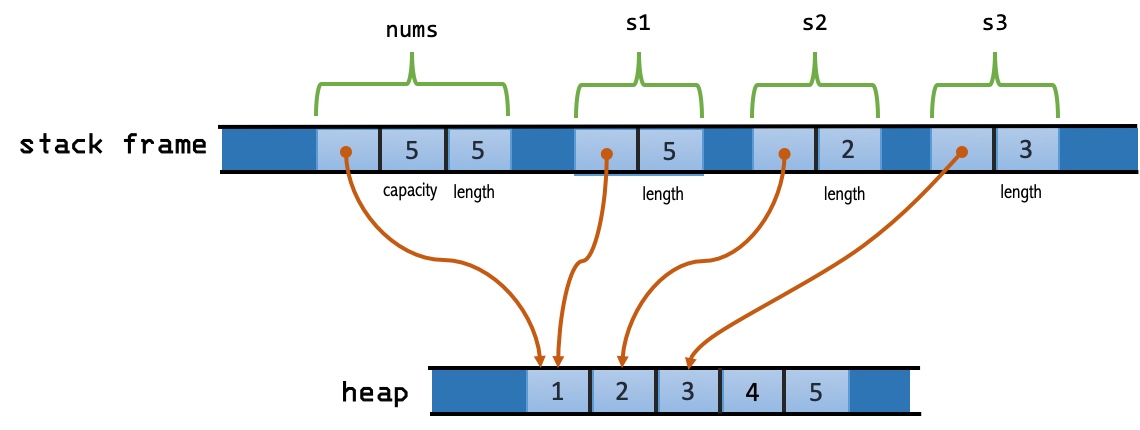

A vector consists of three parts: a pointer to the buffer on the heap to store the elements, the number of the current elements - the length, the total memory space currently occupied on the heap - the capacity. A reference to slice consists of a pointer to the first element of the slice, and the number of elements in the slice - the length.

In the following snippets, a vector named nums contains five elements. Three references of slices s1, s2 and s3 are created based on nums.

fn main() {

let nums = vec![1, 2, 3, 4, 5];

let s1 = &nums[..]; // all emements

let s2 = &nums[1..3]; // range of elements starting from index position 1 to 3 exculsively

let s3 = &nums[2..]; // range of elements starting from index position 2

println!(

"nums: {:?}, capacity: {}, length: {}",

nums,

nums.capacity(),

nums.len()

);

println!("s1: {:?}, length: {}", s1, s1.len());

println!("s2: {:?}, length: {}", s2, s2.len());

println!("s3: {:?}, length: {}", s3, s3.len());

}

🦀 Output:

nums: [1, 2, 3, 4, 5], capacity: 5, length: 5

s1: [1, 2, 3, 4, 5], length: 5

s2: [2, 3], length: 2

s3: [3, 4, 5], length: 3

How nums, s1, s2 and s3 exist on memory is illustrated in the following diagram.

Struct is a simple aggregate of named values. We can also define methods for struct. The first parameter of struct’s method is always self. We can also define associated function which doesn’t take self as a parameter. Associated functions are similar to static methods of a class in Java or C#. In the following, new is an associated function. Associated functions are called with :: operator.

fn main() {

let mut pos = Position::new();

pos.move_to(2.5, 7.5);

}

pub struct Position {

x: f64,

y: f64,

}

impl Position {

pub fn new() -> Position {

Position { x: 0.0, y: 0.0 }

}

pub fn move_to(&mut self, nx: f64, ny: f64) {

self.x = nx;

self.y = ny;

println!("New position: ({},{})", self.x, self.y);

}

}

🦀 Output:

New position: (2.5,7.5)

&mut means pos instance is mutably borrowed by move_to function. In other words, pos instance is passed by reference to move_to function.

Struct like Position is called named struct. There are another two more kinds of struct - tuple-like and unit-like struct like below.

pub struct Port(u16); // tuple-like struct

pub struct Empty; // unit-like struct

Enum can be used if we need a common type for a group of related values. For instance, On and Off are two possible states of a light switch. We can model it in enum as follow:

enum SwitchState{

On,

Off

}

Each enum value can have a different set of fields. Methods can be defined for enum too.

In the following Shapes enum, Circle(f64) and Triangle(f64,f64) variants have tuple-like unnamed fields and Rectanble{ width: f64, height: f64} has struck-like named fields. A method Area is defined within impl Shapes block. In Area method, Shapes values and their fields can be retrieved via pattern match.

#[derive(Debug)]

enum Shapes {

Circle(f64),

Triangle(f64, f64),

Rectangle{ width : f64, height : f64},

}

impl Shapes{

fn area(&self) -> f64{

match *self{

Shapes::Circle(r) => std::f64::consts::PI * r * r,

Shapes::Triangle(h,b) => 0.5 * h * b,

Shapes::Rectangle{ width: w , height: h} => w * h

}

}

}

fn main() {

let circle = Shapes::Circle(10_f64);

println!("Area of {:?} = {}", circle, circle.area());

let triangle = Shapes::Triangle(12_f64, 33_f64);

println!("Area of {:?} = {}", triangle, triangle.area());

let rect = Shapes::Rectangle{ width : 10_f64, height: 11_f64} ;

println!("Area of {:?} = {}", rect, rect.area());

}

🦀 Output:

Area of Circle(10.0) = 314.1592653589793

Area of Triangle(12.0, 33.0) = 198

Area of Rectangle { width: 10.0, height: 11.0 } = 110

Enum can be generic. Rust standard library has a very handy type called Option<T>. <T> is a generic type parameter.

pub enum Option<T>{

Some(T),

None,

}

By using Option type extensively, Rust totally removes the infamous NULL. In most of the standard imperative languages, NULL is used to express lacking of a value or undefined one. The problem is compiler doesn’t enforce programmers of those languages to check NULL state - which might introduce bugs. The following program will use the basic usage of Option type.

fn try_divide(dividend: i32, divisor: i32) -> Option<i32> {

if divisor == 0 {

None

} else {

Some(dividend / divisor)

}

}

fn main() {

let result = try_divide(10, 2);

match result{

Some(r) => println!("Result = {}", r),

None => println!("Not divisiable")

}

}

🦀 Output

Result = 5

str is primitive string type in Rust. str is also called string slice and is always valid UTF-8. Like slice [T], str can not exist on its own. It lives behind a pointer. String literals are string slices.

let greet = “Hello, World!”;

The type of greet is &’static str. ‘static means static lifetime. “Hello, World!” will be directly stored in the final output binary and greet is pointing to the memory location of it at runtime.

String type is provided in standard library. It is UTF-8 encoded string type and, like vector, growable. It actually is a wrapper of Vec<u8>. The following snippet shows how to create String and how to convert from &str to String.

fn main() {

let greet: &'static str = "Hello, World!";

let mut greet_string = greet.to_string();

greet_string.push_str(" I'll tell you one thing.");

println!("{}", greet_string);

let one_thing = String::from("It's a cruel, cruel world.");

println!("{}", one_thing);

}

🦀 Output:

Hello, World! I'll tell you one thing.

It's a cruel, cruel world.

Control Flow

Rust code are executed from top to bottom. For the control of the flow of code execution, Rust supports some constructs: if and loop expressions. Please note that if and loop expressions, not if and loop statements because they return values! Rust is expression language. It is notable that Rust doesn’t have C-Style for loop (for i=0; i < 7; i++). The following code snippet will show the syntax and usage of if, if let, while, while let and loop expressions.

fn main() {

let n = 10;

// the following if expression return () which is of unit type.

if n % 2 == 0 {

println!("{} is even.", n);

} else {

println!("{} is odd.", n);

}

// if semicolon is omitted in final expression of a block,

// the value of the expression will be returned.

let x = if n % 2 == 0 {

"even" // same as return "even";

} else {

"odd" // same as return "odd";

};

println!("{}", x);

let maybe = Some(10);

if let Some(v) = maybe /* v is declared and bound to 10 here */

{

print!("{} ", v);

}

let mut i = 5;

// count down to 0

while i >= 0 {

print!("{} ", i);

i -= 1;

}

print!("\n");

let mut vec = vec!["red", "dead", "redemption", "II"];

// loop and print each word from vec

while let Some(v) = vec.pop() /* pop return Option<T> */

{

print!("{} ", v);

}

print!("\n");

let mut j = 10;

// count down to 0

loop {

if j < 0 {

break;

}

print!("{}", j);

j -= 1;

}

// loop can return value, y will have 10

let y = loop {

break 10;

};

println!("{}", y);

let mut sum = 0;

// the sum of 1 to 10 using for loop

for i in 1..=10 {

sum += i;

}

println!("{}", sum);

}

🦀 Output:

10 is even.

even

10 5 4 3 2 1 0

II redemption dead red

10987654321010

55

Memory safety

Rust is almost all about memory safety. Rust does not allow program code to access invalid memory locations such as uninitialized variables, deallocated data, and out-of-bound access to an array. Rust also ensures to not occur conflicting memory access potentially caused by the condition where the same memory location is accessed by more than one variables with overlapping lifetime while at least one variable having write access.

Let me first show a C++ code snippet borrowed from this excellent presentation to demonstrate conflicting memory access.

#include <iostream>

#include <vector>

#include <string>

#include <iomanip>

using namespace std;

int main() {

vector<string> towns = { "Blackwater", "Strawberry"};

string& towns_alias = towns[0];

cout << "Before inserting new item:" << endl;

cout << "towns[0] : " << setw(17) << towns[0] << setw(30)

<< "address of towns[0]: " << &towns[0] << endl;

cout << "towns_alias : " << setw(15) << towns_alias << setw(30)

<< "address of towns_alias: " << &towns_alias << endl << endl;

towns.push_back("Tumbleweed");

cout << "After inserting new item:" << endl;

cout << "towns[0] : " << setw(17) << towns[0] << setw(30)

<< "address of towns[0]: " << &towns[0] << endl;

cout << "towns_alias : " << setw(15) << towns_alias << setw(30)

<< "address of towns_alias: " << &towns_alias << endl << endl;

}

Output:

Before inserting new item:

towns[0] : Blackwater address of towns[0]: 0x7ff182402c80

towns_alias : Blackwater address of towns_alias: 0x7ff182402c80

After inserting new item:

towns[0] : Blackwater address of towns[0]: 0x7ff182402d80

towns_alias : address of towns_alias: 0x7ff182402c80

In the code snippet above, you might notice that:

- two variables

townsandtowns_aliasare pointing to the same memory location townshas read/write access to the data andtowns_aliashas read/write access to the first element of the vector- both

townsandtowns_aliashas overlapping lifetime

It’s perfect situation that could lead to conflicting memory access problem.

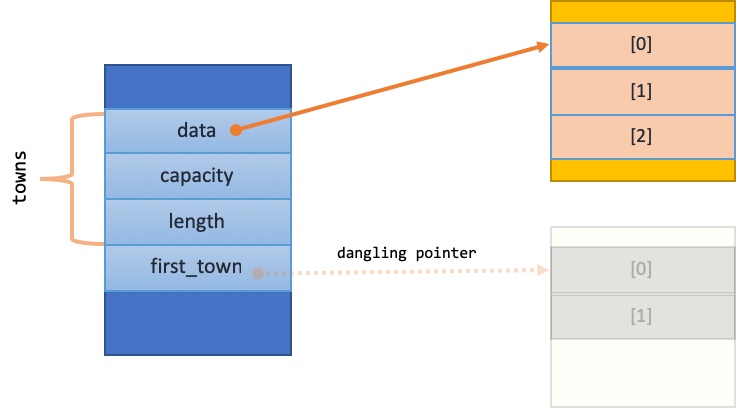

When a new item is inserted to towns vector, due to not having enough capacity, the vector internally creates a new array with enough capacity to accommodate all the items, and then existing items are moved to new location and new item is appended. Now, towns_alias effectively becomes dangling pointer pointing to a deallocated location - which can leads to subtle bugs that can be very hard to find.

The following picture illustrates what towns and towns_alias are pointing to after mutation.

You may notice, in the last line of the output, cout function prints blank for towns_alias and towns having new memory address after mutation.

We have already observed that conflicting memory access can occur If all of the following conditions are met:

- More than one variables access the same memory location

- At least one has a write access

- They have overlapping lifetime

Rust’s Ownership system effectively solves the problem by enforcing programmer to obey the following rules. If programmers don’t obey the rules, Rust will punish them by not compiling their code. The reward of obeying the rules is you will have memory-safety with zero-cost and deterministic memory management. Zero-cost means you don’t need to pay for Garbage Collector at all. No Garbage Collector means you get deterministic memory management.

Ownership rules are as follows:

- Each value has one owner variable at a time

- When owner goes out of scope, the value will be dropped.

- At any one time, within valid lifetime, either a value can be mutably shared to only one variable or a value can be immutably shared to multiple other variables

The following code snippet demonstrates Rule 1 and 2.

fn main() {

let towns = vec!["Blackwater", "Strawberry"];

print_town_names(towns);

/*

error occurs at the following line

because the ownership of 'towns' is already moved to

the parameter 'tw' of print_town_names function

*/

println!("{:?}", towns);

}

fn print_town_names(tw : Vec<&str> ){

for t in &tw{

println!("{}", t);

}

}

Rust compiler will complain about the code above. A vector containing two string elements "Blackwater", "Strawberry" has an owner called towns. The ownership of towns is moved to a new owner called tw when the function print_town_names is called. At the end of print_town_names function, the variable tw goes out of scope and the data of tw on the heap is dropped or deallocated. Back in the main function, towns is used again - that’s the reason we are getting compile time error. Rust’s static analysis can catch dangling pointer like towns and gives user compile time error like below.

🦀 Output:

Compiling memory_safety v0.1.0 (/Users/nyinyithan/rust-playground/memory_safety)

error[E0382]: borrow of moved value: `towns`

--> src/main.rs:7:22

|

3 | print_town_names(towns);

| ----- value moved here

...

7 | println!("{:?}", towns);

| ^^^^^ value borrowed here after move

|

= note: move occurs because `towns` has type `std::vec::Vec<&str>`, which does not implement the `Copy` trait

We can fix the code above. Remember rule 3 - we can immutably shared a value to multiple variables if there is no mutable share of the value at any give time. We will fix the code by immutably sharing towns to print_town_names function. & symbol is used to describe reference to a value. &towns means the reference to towns vector. The signature of print_town_names needs to be updated - &Vec<&str> instead of Vec<&str>. As a side note, &T actually is a const pointer *const T.

fn main() {

let towns = vec!["Blackwater", "Strawberry"];

print_town_names(&towns);

println!("towns in main : {:?}", towns);

}

fn print_town_names(tw : &Vec<&str> ){

println!("towns in print_town_names :");

for t in tw{

println!("\t{}", t);

}

}

🦀 Output:

towns in print_town_names :

Blackwater

Strawberry

towns in main : ["Blackwater", "Strawberry"]

If we want to modify the vector within print_town_names, we can do it by mutably sharing towns with &mut. Note that the original variable towns has to be changed to mutable one. In the following code, we add a new town to the vector within print_town_names function.

fn main() {

let mut towns = vec!["Blackwater", "Strawberry"];

print_town_names(&mut towns);

println!("towns in main : {:?}", towns);

}

fn print_town_names(tw : &mut Vec<&str> ){

println!("towns in print_town_names :");

tw.push("Tumbleweed");

for t in tw{

println!("\t{}", t);

}

}

🦀 Output:

towns in print_town_names :

Blackwater

Strawberry

Tumbleweed

towns in main : ["Blackwater", "Strawberry", "Tumbleweed"]

As rule 3 states, we cannot both mutably and immutably share a value within the same scope. The following code will not be compiled.

fn main() {

let mut towns = vec!["Blackwater", "Strawberry"];

let share = &towns; // immutable reference

let share_mut = &mut towns; // mutable reference

println!("{:?} {:?}", share, share_mut);

}

🦀 Output:

error[E0502]: cannot borrow `towns` as mutable because it is also borrowed as immutable

--> src/main.rs:5:21

|

4 | let share = &towns;

| ------ immutable borrow occurs here

5 | let share_mut = &mut towns;

| ^^^^^^^^^^ mutable borrow occurs here

6 |

7 | println!("{:?} {:?}", share, share_mut);

| ----- immutable borrow later used here

It is important to note that Rust doesn’t transfer ownership of the value allocated on the stack when it is assigned to other variables or passed to functions as arguments.

In the code below, vector v is allocated on the heap. When v is assigned to v2, the ownership is transferred to v2.

let v = vec![1, 2, 3, 4];

let v2 = v;

In the code below, i is allocated on the stack. When i is assigned to i2, the actual value is copied to i2 instead of transferring ownership.

let i : i32 = 10;

let i2 = i;

Rust allocates types with a known size at compile time on the stack. On the other hands, dynamically sized types are stored on the heap. Copying values of heap-allocated types all the time is not efficient. One thing to note is that all the stack-allocated types implement Copy trait through which Rust copies the values of them. If you implements Copy trait on your own types, they will get copy semantics too.

Trait and Generic

Trait is basically a set of methods with or without implementation. Trait can also have associated methods, associated type fields and associated constants. Trait is generally similar to interface or abstract class in other languages, but more powerful. Trait is mainly inspired by Haskell’s typecalss. Trait plays very important role in Rust’s type system. The following code snippet shows the creation and basic usages of trait.

trait Gunslinger {

fn shoot(&self);

fn talk(&self);

}

trait Age {

fn get_age(&self) -> u8;

}

struct Cowboy {

name: String,

age: u8,

}

impl Gunslinger for Cowboy {

fn shoot(&self) {

println!("{} shoots - bang! bang! bang!", self.name);

}

fn talk(&self) {

println!(

"{} says 'If you find yourself in a hole, the first thing to do is stop digging'.",

self.name

);

}

}

impl Age for Cowboy {

fn get_age(&self) -> u8 {

self.age

}

}

struct Lawman {

name: String,

age: u8,

title: String,

}

impl Gunslinger for Lawman {

fn shoot(&self) {

println!("{} {} shoots - pow! pow! pow!", self.title, self.name);

}

fn talk(&self) {

println!("{} {} says 'It's better to keep your mouth shut and look stupid than open it and prove it'.",

self.title, self.name);

}

}

impl Age for Lawman {

fn get_age(&self) -> u8 {

self.age

}

}

fn show_down<T>(dude: &T)

where

T: Gunslinger + Age,

{

if dude.get_age() >= 65 {

dude.talk();

} else {

dude.shoot();

}

}

fn main() {

println!("***Generic with Trait Bound***");

let alfred = Lawman {

name: String::from("Alfred Shea Addis"),

age: 40,

title: String::from("Marshal"),

};

show_down(&alfred);

let mariano = Lawman {

name: String::from("Mariano Barela"),

age: 70,

title: String::from("Sheriff and U.S. Marshal"),

};

show_down(&mariano);

let james = Cowboy {

name: String::from("Jesse James"),

age: 30,

};

show_down(&james);

let earl = Cowboy {

name: String::from("Earl W. Bascom"),

age: 80,

};

show_down(&earl);

println!("\n***Triat Object***");

let mut gs: &dyn Gunslinger = &alfred;

gs.talk();

gs = &earl;

gs.talk();

}

🦀 Output:

***Generic with Trait Bound***

Marshal Alfred Shea Addis shoots - pow! pow! pow!

Sheriff and U.S. Marshal Mariano Barela says 'It's better to keep your mouth shut and look stupid than open it and prove it'.

Jesse James shoots - bang! bang! bang!

Earl W. Bascom says 'If you find yourself in a hole, the first thing to do is stop digging'.

***Triat Object***

Marshal Alfred Shea Addis says 'It's better to keep your mouth shut and look stupid than open it and prove it'.

Earl W. Bascom says 'If you find yourself in a hole, the first thing to do is stop digging'.

There are two traits Gunslinger and Age. Both Cowboy and Lawman structs implement Gungslinger and Age. Types in Rust can implement any amount of Traits without overhead. show_down function accepts any type which implements both Gunslinger and Age traits. In show_down function, T is a trait bound generic type parameter. Rust will generate specialized versions for functions with trait bound generic. In our case, Rust will generate two copies of show_down function, one with Lawman type and another with Cowboy type because we call show_down function with both of those types. Trait is statically dispatched in this case.

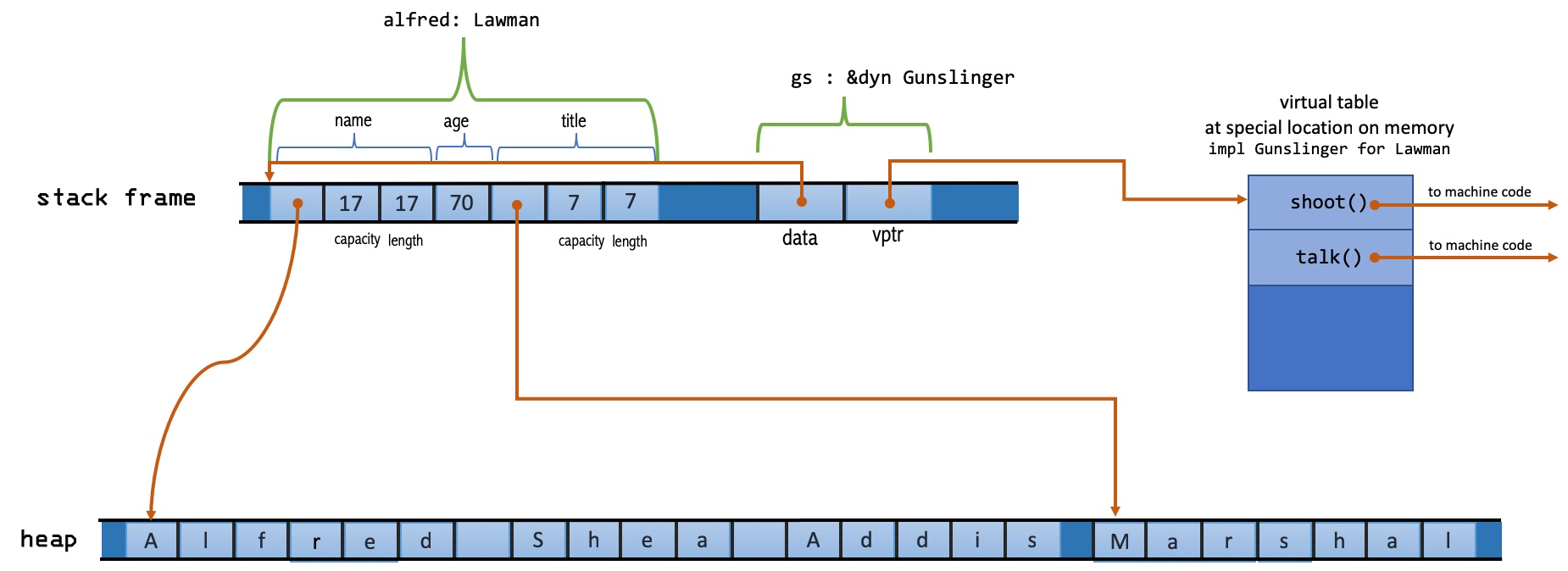

Another usage of trait is via trait object. Because the size of trait object cannot be determined at compile time, Rust considers trait object as dynamically sized type. Like slice, trait object cannot stand on its own, and needs to show up behind a pointer. In the above code snippet, a trait object gs is created and assigned with a reference to Lawman type &alfred first and calls talk method. And then it is assigned with a reference to Cowboy type &earl and calls talk method. We can do so because Gunslinger trait is implemented by both Cowboy and Lawman type. Rust decides at runtime which talk method will be called. Trait is dynamically dispatched with trait object.

A trait object is a fat pointer consisting of a pointer to the value and another pointer to virtual method tables of the type of the value.

let mut gs: &dyn Gunslinger = &alfred; //alfred is of type Lawman

Memory allocation of the above code can be illustrated like below.

Not only can traits be used as function arguments, but trait can also be returned from a function.

fn get_a_gunslinger() -> impl Gunslinger{

Cowboy{

name: String::from("Blackwater Wolf"),

age: 39,

}

}

Trait can also be used to extend existing types. It is not merely adding new methods to existing types like C#’s extension method does, we can even implement our own traits on existing built-in or third-party types! The following snippet demonstrates how to extend Option<T> type found in standard library. We are adding a new method fold to Option<T>. We here introduce a new trait called OptionExt<T>.

use std::borrow::BorrowMut;

pub trait OptionExt<T> {

fn fold<S, F>(&self, state: S, folder: F) -> S

where

F: FnOnce(S, &T) -> S;

}

impl<T> OptionExt<T> for Option<T> {

fn fold<S, F>(&self, state: S, folder: F) -> S

where

F: (FnOnce(S, &T) -> S),

{

match self {

Some(x) => folder(state, &x),

None => state,

}

}

}

fn main() {

let opt = Some(10);

let opt_sum = opt.fold(1, |s, x| s + x);

println!("opt_sum = {}", opt_sum);

let opt_list = Some(1..=10);

let opt_list_sum =

opt_list.fold(0, |s, x| x.clone().borrow_mut().fold(s, |acc, y| acc + y));

println!("opt_list_sum = {}", opt_list_sum);

}

🦀 Output:

opt_sum = 11

opt_list_sum = 55

A trait can also extend another traits. In the following code snippet, UIElement trait extends MarshalByRef and Visual. Because Control struct implements UIElement, it needs to implement UIElement’s super traits too - Visual and MarshalByRef. MarshalByRef is empty trait and usually called marker trait. Rust has some built-in marker traits e.g Send and Sync used in multi-threading.

pub trait MarshalByRef {}

pub trait Visual {

fn point_to_screen(&self);

}

pub trait UIElement: MarshalByRef + Visual {

fn arrange(&self);

fn focus(&self);

}

pub struct Control {

padding: (f32, f32, f32, f32),

border_thickness: f32,

}

impl Control {

fn new() -> Control {

Control {

padding: (1_f32, 1_f32, 3_f32, 3_f32),

border_thickness: 1.2_f32,

}

}

}

impl UIElement for Control {

fn arrange(&self) {

println!("arrange");

}

fn focus(&self) {

println!("focus");

}

}

impl Visual for Control {

fn point_to_screen(&self) {

println!("point_to_screen");

}

}

impl MarshalByRef for Control {}

fn main() {

let ctrl = Control::new();

ctrl.point_to_screen();

ctrl.arrange();

ctrl.focus();

}

🦀 Output:

point_to_screen

arrange

focus

Trait is also used in operator overloading, type conversion, type coercion, iteration, closures and others. Trait is everywhere in Rust. I will write some follow-up posts on traits in detail sometime.

Function and Closure

We can create functions in Rust by using fn keyword followed by function name, arguments within parenthesis, an arrow “->” with return type like below:

fn add(x : i32, y : i32) -> i32{ x + y}

Rust is expression language. All expression return a value. Function invocation in Rust is called Call expression. Meaning all function invocation return a value. The following print_hello function returns a value which is of unit type. Unit type has a single value and it is indicated by the token (). If a function returns unit, the return type can be omitted in function signature.

fn print_hello() {

println!("hello");

}

fn main() {

let r = print_hello();

dbg!(r);

}

🦀 Output:

hello

[src/main.rs:6] r = ()

fn is of function pointer type. Basically it is the same as function pointer in C/C++. Function can be specified with unsafe keyword if it is accessing unsafe features or extern keyword if it is calling external code written in other languages. Rust does not support function overloading where the same method is defined with multiple signatures. Rust also has no variadic function that takes variable numbers of parameters.

Functions can be bound to identifiers, passed as parameters, or returned by functions. The following code snippet demonstrates the feature.

fn add(x: i32, y: i32) -> i32 {

x + y

}

fn do_add(a: i32, b: i32, f: fn(i32, i32) -> i32) -> i32 {

f(a, b)

}

fn return_add() -> (fn(i32, i32) -> i32) {

add

}

fn main() {

// 'add' function is bound to 'adder' identifier,

// 'fn(i32, i32) -> i32' is the type of 'add' function

let adder: fn(i32, i32) -> i32 = add;

dbg!(adder(1, 2));

// 'add' function is pass as an argument

dbg!(do_add(1, 3, add));

// 'add' function is returned from 'return_add'

dbg!(return_add()(1, 2));

}

🦀 Output:

[src/main.rs:17] adder(1, 2) = 3

[src/main.rs:19] do_add(1, 3, add) = 4

[src/main.rs:21] return_add()(1, 2) = 3

Closures are similar to functions, but they can capture or access variables from their environments. Closures are not function pointers, instead they are under the hood anonymous structs which implement Fn and FnMut or FnOnce trait. Closure syntax includes || for input parameters, {} for closure body which is optional for a single expression.

Closures that have read-access to their environment variables implement Fn trait. In the following snippet, fn_closure gets read-access to nums vector which is still accessible after invoking the closure.

fn main() {

let nums = vec![1, 2, 3, 4, 5];

let fn_closure = || {

println!("fn_closure nums : {:?}", nums);

};

invoke_closure(fn_closure);

println!("main nums : {:?}", nums);

}

fn invoke_closure<F:Fn()> (func : F){

func();

}

🦀 Output:

fn_closure nums : [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

main nums : [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

Closures that mutate the value of captured variables implement FnMut trait. Rust compiler inspects the closure code and implement the corresponding trait. In the following snippet, nums vector is updated inside the closure. Therefore, compiler implements FnMut trait on fn_mut_closure.

fn main() {

let mut nums = vec![1, 2, 3, 4, 5];

let mut fn_mut_closure = || {

for n in &mut nums{

*n += 1;

}

println!("fn_mut_closure nums : {:?}", nums);

};

invoke_closure(&mut fn_mut_closure);

println!("main nums : {:?}", nums);

}

fn invoke_closure<F: FnMut()> (func : &mut F){

func();

}

🦀 Output:

fn_mut_closure nums : [2, 3, 4, 5, 6]

main nums : [2, 3, 4, 5, 6]

if a closure takes the ownership of its environment variables, Rust compiler will implement FnOnce trait on it. In the following snippet, fn_once_closure takes the ownership of greet variable. fn_once_closure closure can be invoked exactly once. If it is invoked more than once the program will panic. FnOnce closure is used in spawning threads - thread::spwan method. Another usage is to drop the captured variables within closure.

fn main() {

let greet = String::from("hello ");

let fn_once_closure = |name : &str| {

greet + name

};

invoke_closure(fn_once_closure);

// will throw error cause fn_once_closure is FnOnce and cannot be called more than once

// invoke_closure(fn_once_closure);

// will throw error her cause greet is already moved into fn_once_closure.

// println!("main x : {:?}", greet);

}

fn invoke_closure<F: FnOnce(&str) -> String> (func : F){

println!("{}", func("James"));

}

🦀 Output:

hello James

Iterator

An iterator supplies the values of a sequence one at a time. If you need to perform some operations on the elements of a sequence, you would need to use several different iterators in Rust. All the iterators in Rust implement the Iterator trait. The core of Iterator trait looks like this:

trait Iterator {

type Item;

fn next(&mut self) -> Option<Self::Item>;

}

type Item is called an associated type, and it is the type of the iterator’s element. next method will return Option type - Some(Item) if next time exists, otherwise, None. If a type implements Iterator, the standard way to get it from the type is to call iter() or iter_mut() or into_iter() methods. Vec implements Iterator, and it will be used in the following code snippets to learn about iterator. All the collection types in standard library implements Iterator and you can apply the same techniques to them.

In the snippet below, iter() method of vector v will return the iterator that takes element of v by shared reference - meaning the value returned from next() method cannot be mutated.

fn main() {

let v = vec![1, 2, 3];

let mut iter = v.iter();

dbg!(iter.next());

dbg!(iter.next());

dbg!(iter.next());

dbg!(iter.next());

}

🦀 Output:

[src/main.rs:4] iter.next() = Some(1)

[src/main.rs:5] iter.next() = Some(2)

[src/main.rs:6] iter.next() = Some(3)

[src/main.rs:7] iter.next() = None

In the snippet below, iter_mut() method of vector v will return the iterator that takes element of v by mutable reference - meaning the value returned from next() method can be mutated. iter_mut() method requires v to be mutable variable.

fn main() {

let mut v = vec![1, 2, 3];

let mut iter = v.iter_mut();

while let Some(n) = iter.next(){

*n *= 10;

}

println!("v = {:?}", v);

}

🦀 Output:

v = [10, 20, 30]

There is another trait called IntoIterator which has into_iter() method that can be used to convert into Iterator. A type that implements IntoIterator works with Rust’s for-in loop syntax. Because vector type implements IntoIterator, we can use vector with for-in loop like below:

fn main() {

let v = vec![1, 2, 3];

for i in v{

print!("{} ", i);

}

}

🦀 Output:

1 2 3

for-in loop is actually syntactic sugar over calling into_iter(), and then next() method of the returned iterator. Upon compilation, Rust might desugar the above for-in loop as follow (might not be exactly like the code below, just to get the idea):

fn main() {

let v = vec![1, 2, 3];

let mut iter = v.into_iter();

while let Some(i) = iter.next(){

print!("{} ", i);

}

}

🦀 Output:

1 2 3

The kind of iterator returned from into_iter() method depends on the context. If you call the method on the vector itself, like in the code snippet above, into_iter() method will return an iterator that takes ownership of the vector. After looping, the vector can no longer be accessed. You will receive error when you compile the following snippet.

fn main() {

let v = vec![1, 2, 3];

for i in v{

print!("{} ", i);

}

println!("{}", v); // error here

}

Compiling playground v0.0.1 (/playground)

error[E0382]: borrow of moved value: `v`

--> src/main.rs:6:22

|

3 | for i in v {

| - value moved here

...

6 | println!("{:?}", v); // error here

| ^ value borrowed here after move

|

= note: move occurs because `v` has type `std::vec::Vec<i32>`, which does not implement the `Copy` trait

Calling into_iter() method over shared reference of the vector is the same as calling iter(). The following code works because into_iter() is called over &v.

fn main() {

let v = vec![1, 2, 3];

for i in &v {

print!("{} ", i);

}

println!("\nv = {:?}", v);

}

🦀 Output:

1 2 3

v = [1, 2, 3]

Calling into_iter() method over mutable reference of the vector is the same as calling iter_mut(). The following code works because into_iter() is called over &mut v where v itself is declared as mutable.

fn main() {

let mut v = vec![1, 2, 3];

for i in &mut v {

*i *= 10;

}

println!("\n v = {:?}", v);

}

🦀 Output:

v = [10, 20, 30]

There are lots of other handy methods defined on Iterator trait. They are kind of essential to write idiomatic Rust. The following code snippet will show the basic usage of two methods of Iterator - map and filter.

map can be used to create a new sequence whose elements are the results of applying the given closure to each of the elements of the original sequence. In the code snippet below, a new vector new_v is created by applying a closure that adds 1 to each item of the existing vector v. collect method is called to consume the iterator generated by map method.

fn main() {

let v = vec![1, 2, 3, 4, 5];

let new_v : Vec<_> = v.iter().map(|x| x + 1).collect();

println!("\n v = {:?}", new_v);

}

🦀 Output:

v = [2, 3, 4, 5, 6]

filter can be used to create a new sequence containing only the items of the original sequence for which the given closure returns true.

fn main() {

let v = vec![1, 2, 3, 4, 5];

let new_v : Vec<_> = v.iter().filter(|&x| x % 2 == 0).collect();

println!("\n v = {:?}", new_v);

}

🦀 Output:

v = [2, 4]

Error Handling

Rust doesn’t have exception handling mechanism like Java or C#. Instead, Rust gives us Result<T, E> type for recoverable errors and the panic! macro to stop the execution of the program having unrecoverable errors.

When our program reaches an unrecoverable problem, we should call panic!(). We can also provide panic message like panic!("something is absolutely wrong here");

For recoverable errors, we should return or propagate errors by using Result<T,E> where T is for Ok(T) case and E for Err(E) case. Rust standard library use Result<T,E> extensively for propagating errors. The following code snippet shows how to deal with the result returned by parse function of str type.

use std::num::ParseIntError;

use std::error::Error;

fn main() {

let result: Result<i32, ParseIntError> = "1ad0".parse::<i32>();

match result {

Ok(v) => println!("Parsed value * 2 = {}" , v * 2),

Err(e) => println!("{:?}", e)

}

}

🦀 Output:

ParseIntError { kind: InvalidDigit }

We can also create our own specific error type by implementing built-in std::error::Error trait.

MetaProgramming

Metaprogramming generally means writing code that can observe itself, and manipulates or generates code. Attributes and macros are powerful metaprogramming tools in Rust.

In Rust, attributes are used for conditional compilation, turn on/off compiler features, custom derive, unit test and many more. You can even create your own attributes for specific use cases.

In the following code snippet, we turn on core_intrinsics feature to use type_name method by using feture attribute. core_intrinsics is considered unstable and it is turned off by default.

#![feature(core_intrinsics)]

fn print_type_of<T>(_: &T) {

println!("Type is: {}", unsafe { std::intrinsics::type_name::<T>() });

}

fn main() {

let nums = vec![1, 2, 3, 4, 5];

print_type_of(&nums);

}

🦀 Output:

Type is: std::vec::Vec<i32>

We can also use derive attribute to ask Rust compiler to provide basic implementation for derivable traits such as Eq, PartialEq, Ord, ParitalOrd, Clone, Copy, Hash, Default, Debug. We can also create our own custom derivable traits. In the code below, Meter type is tagged with #[derive(Debug)] - asking compiler to implement Debug trait for Meter type so that we can inspect the type using dbg!() or print it with {:?} format specifier.

fn main() {

let m = Meter::new(3.7);

println!("{:?}", m);

dbg!(m);

}

#[derive(Debug)]

struct Meter(f64);

impl Meter {

fn new(m: f64) -> Meter {

Meter(m)

}

}

🦀 Output:

Meter(3.7)

[src/main.rs:4] m = Meter(

3.7

)

Through out all the code snippets, we see println!, dbg!, vec! a lot. They are macros. Macros can basically be used to generate code. Macros can save us from writing repetitive code again and again.

For example, Instead of writing the following code again and again:

let v = {

let mut temp = Vec::new();

temp.push(1);

temp.push(2);

temp.push(3);

temp

};

We will write:

let v = vec![1, 2, 3];

Below is a simple macro to create two types that implements Default trait.

macro_rules! impl_hash {

($name: ident, $size: expr) => {

#[derive(Debug)]

pub struct $name([u8; $size]);

impl Default for $name {

fn default() -> Self {

$name([0; $size])

}

}

};

}

impl_hash!(H256, 32);

impl_hash!(H160, 20);

fn main() {

let h256 = H256::default();

let h160 = H160::default();

println!("{:?}", h256);

println!("{:?}", h160);

}

🦀 Output:

H256([0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0])

H160([0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0])

macro_rules! impl_hash creates a macro named impl_hash. $name : ident means a valid identifier will be assigned to a metavariable called $name. $size: expr means valid Rust expression will be assigned to a metavariable called $size. You may notice pattern matching syntax here. The matching happens on Rust syntax tree at compile time. Upon valid matching, our little macro will generate the code within the right-side block with the substitution of $name and $size.

Unsafe Rust

Rust has a very powerful feature to offer its users. It is called unsafe. The power is given to users, if they don’t use it responsibly, they become unsafe - all the bad things like memory leakage, dangling pointers, segmentation fault, dead lock, null pointer can happen. On the other hand, With unsafe, users can perform dereferencing raw pointers - *const T and *mut T, calling unsafe methods, implementing unsafe traits, and modifying mutable static variables.

Below are some code snippets to show you how we can use raw pointers in unsafe Rust. The first code snippet is in C language - simple addition of tow integer pointers. The second snippet is in unsafe Rust - simple addition of two integer pointers which are allocated on the heap using C Standard Library (libc), without using any of Rust standard library APIs. The second code snippet is, we can say that, C in Rust syntax. We can have all the power of C in Rust if we need.

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

int main() {

int* ptr1 = (int*) malloc(sizeof(int));

if(ptr1 == NULL){

printf("Memory not allocated.");

exit(0);

}

*ptr1 = 2;

int* ptr2 = (int*) malloc(sizeof(int));

if(ptr2 == NULL){

printf("Memory not allocated.");

exit(0);

}

*ptr2 = 5;

printf("%d + %d = %d\n",*ptr1, *ptr2, *ptr1 + *ptr2);

free(ptr1);

free(ptr2);

return 0;

}

Output:

2 + 5 = 7

The following is unsafe Rust calling all the same C functions above - malloc, free, printf, exit.

#![feature(start)]

#![no_std] // Truning off Rust Standard library

extern crate libc;

use core::panic::PanicInfo;

use libc::{c_char, c_int, c_void, size_t};

extern "C" {

fn malloc(size: size_t) -> *mut c_void;

fn free(p: *mut c_void);

fn exit(status: c_int) -> !;

fn printf(fmt: *const c_char, ...) -> c_int;

}

#[start]

fn main(argc: isize, _argv: *const *const u8) -> isize {

unsafe {

let ptr1 = malloc(32 as size_t) as *mut i32;

if ptr1 as usize == 0 {

printf("Memory not allocated.\0".as_ptr() as *const i8);

exit(0);

}

*ptr1 = 2;

let ptr2 = malloc(32 as size_t) as *mut i32;

if ptr2 as usize == 0 {

printf("Memory not allocated.\0".as_ptr() as *const i8);

exit(0);

}

*ptr2 = 5;

printf(

"%d + %d = %d\0".as_ptr() as *const i8,

*ptr1,

*ptr2,

*ptr1 + *ptr2,

);

free(ptr1 as *mut c_void);

free(ptr2 as *mut c_void);

}

0

}

#[panic_handler]

fn panic(_info: &PanicInfo) -> ! {

loop {}

}

🦀 Output:

2 + 5 = 7

Summary

With the grantee of memory safety without Garbage Collector alone, I consider Rust is fantastic. On top of memory safety, Rust offers rich type system, zero-cost abstraction, pragmatic error handling, concurrency safety, Functional Programming constructs. I find programming in Rust is a great fun.

Thanks for reading.